What is aortic valve regurgitation?

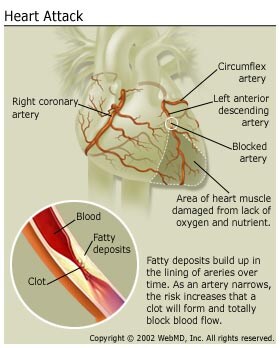

Aortic valve regurgitation develops when the does not function correctly. To understand this condition, it's helpful to know how the aortic valve normally functions. The aortic valve works like a one-way gate, opening so that blood from the left ventricle (the heart's main pump) can be pushed into the , the large artery leaving the heart. From the aorta, oxygen-rich blood flows into the branching arteries and through the body to feed the cells. When the heart rests between beats, the aortic valve closes to keep blood from flowing backward into the heart. See a picture .

In aortic valve regurgitation, the aortic valve does not close properly. With each heartbeat, some of the blood pumped into the aorta leaks back (regurgitates) through the faulty valve into the left ventricle. The body doesn't receive enough blood, so the heart must work harder to make up for it (compensation). See a picture of

Typically, symptoms do not develop for decades because the heart compensates by getting bigger so that it can pump out more blood. But, if it is not corrected, regurgitation usually gets worse over time, and symptoms such as shortness of breath and fatigue develop. At this point, an aortic valve replacement is typically needed to prevent (arrhythmias), and irreversible damage to the heart muscle.

In rare cases, aortic valve regurgitation comes on suddenly and requires immediate medical attention.

Some people have very small amounts of blood that leak back into the left ventricle. This usually doesn't cause any symptoms or problems. This topic focuses on the more serious cases of aortic valve regurgitation where large amounts of blood flow back across the aortic valve into the left ventricle.

What causes aortic valve regurgitation?

Any condition that damages the aortic valve can cause aortic valve regurgitation. Common causes include being born with a defective aortic valve, wear and tear from aging, infection of the lining of the heart and . Enlargement of the aorta, associated with and hardening of the arteries , can also cause aortic valve regurgitation. On rare occasions, to the chest can damage the aortic valve.

Rarer conditions that cause aortic valve regurgitation include a disorder of the body's connective tissues, a type of arthritis, some, and.

The most common causes of sudden (acute) aortic valve regurgitation include:

- Endocarditis, which is an infection in the heart caused by bacteria.

- which is the separation of the inner layer of the aorta from the middle layer.

- Problems with the.

Other conditions that cause acute regurgitation include trauma to the heart valve.